Public policy recommendations are one way academics seek to influence the world. That said, I fear we often don’t give our recommendations much thought. They are tacked onto the end of papers to make the years of work done on the problem seem important enough to publish. This week, rather than look at a paper with a public policy recommendation, I’ll turn to a related problem. An expert, rightly widely respected by the public, who took a similarly casual attitude when addressing a public policy question. Experts, whether they be academics or a Dame of the British Empire with a major institute supporting her good work, need to think through their comments on public policy. Experts need to take public policy interventions seriously.

The Carbon Tax

Jane Goodall recently wandered into a major political debate in Canada. As someone who is worried about climate change, she might have been expected to be supportive of the carbon tax. She is exactly the sort of widely respected person who could help explain the policy. She could even make constructive suggestions for improving bits of the law. That wasn’t what she did.

When she gave her thoughts on this contentious topic she was negative. If she had specific expertise on the subject of carbon taxes and her comments were insightful then it is entirely appropriate to say what is wrong even if it upsets those she might be expected to support. The problem with Goodall’s intervention is that she put the boot into people on her side and didn’t make much sense.

What Does A Tax Do?

To be clear Goodall doesn’t make a nuanced argument about the problems in a specific carbon tax, like the one in Canada. No scheme anywhere is perfect, so there are definitely things that could be changed. Indeed, I would guess even supporters of the Canadian carbon tax would agree that the communication of the plan appears not to have worked well given it is noticeably unpopular.

Still, Goodall comes at it from a different angle and dismisses the idea of a carbon tax in two ways. First, by understating what it does. Second, by saying it doesn’t do everything.

“The problem with a climate tax is that, yes, it can do some good — it gives money to control climate change and so on — but it doesn’t get to the root cause, which is fossil fuel emissions, emissions of methane from industrial farming,” she said. “So, in that sense, it’s not something I endorse.”

Jane Goodall quoted in Tasker (2024)

Let’s tackle the second argument first. That the carbon tax doesn’t do everything. This is technically correct. Does a tax on fossil fuels tackle methane from industrial farming? No, but what policy tackles everything? It is like dismissing the idea of laws against burglary because it won’t stop insider trading.

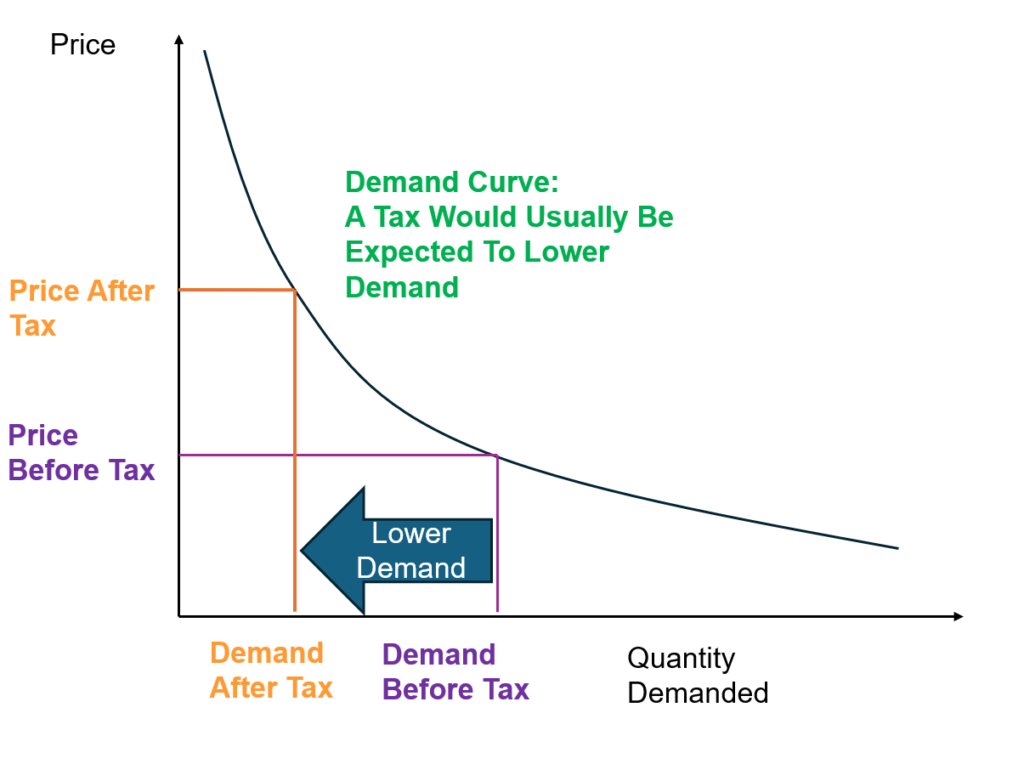

Even stranger is the idea that the tax will only give money to control climate change and won’t impact fossil fuel emissions. A tax raises the price of a good. When prices go up, people typically look for ways to use less. It would be quite odd if a carbon tax didn’t reduce demand for fossil fuels at all. Indeed, such a reduction may be the main reason to implement the carbon tax, yet, she suggests it won’t impact fossil fuel emissions. Surely it will. I would think even thoughtful critics of the carbon tax think it will reduce emissions, they just think the cost of the emissions reduction is too high for the benefits it brings.

What If Demand Is Inelastic Or Oil Companies Are Too Rich To Care?

Inelastic demand is when demand doesn’t change much when the price changes. In the short term, people just pay more because they can’t change their behavior. Yet, even with the most inelastic demand people usually change behavior eventually. Cigarette taxes have surely discouraged smoking and nicotine is an addictive substance that is physically hard to quit. Taxes may be expected to change behavior at least in the long-run. Plus, in the short-run the government raises money that they can invest in clean energy or give back to consumers.

She also suggests that oil companies are making so much money they won’t be impacted by any tax. But surely that is an argument for a higher tax. It would be a perfect world where government could raise a tax to a higher level and those paying it didn’t notice any difference. The government would then be able to raise loads of money painlessly that they could subsidize clean energy benefiting the consumers. And, of course, that would also limit demand for fossil fuels. Who would buy dirty fuels when heavily subsidized clean fuels are much cheaper? We get to less fossil fuel use just by a different route. Sounds good to me.

What Is Goodall’s Plan?

“We need to curb it everywhere. I have great faith in young people — they’re beginning to understand and they can affect their parents who may be in the oil business,”

Jane Goodall quoted in Tasker (2024)

Goodall seems to be relying on the children of people in the oil industry being a positive influence on them. That doesn’t sound like a practical policy suggestion to me. She is against an actual policy designed to help address a problem she agrees is critically important to address. Instead, she seems to want to replace it with wishful thinking. Goodall argues that the oil companies are making lots of money so surely they will be very hard to convince. Maybe the oil executives will buy their kids a new car or a pony with all the money they are making and the kids will stop pestering their parents.

Experts Need To Take Public Policy Interventions Seriously

So what happens next? The carbon tax is unpopular in Canada, and with “Climate Warriors” like Goodall not supporting it that doesn’t seem likely to change. I can predict the next move. The politicians will ditch the policy or, at least, water it down significantly. Then someone like Goodall will castigate politicians for having no courage. The public will then tut about not getting the politicians we deserve. Yet, any sensible politician will keep their heads down knowing that, if things get tough, even their friends won’t support them.

Surely good public policy at a national level can achieve more positive difference to the world than even Goodall’s institute, so why didn’t she support a policy she might have been expected to? Did she see the way the political wind was blowing, decide she didn’t want to be unpopular and so wouldn’t support the carbon tax? Or had she not thought much about public policy but still decided to share her views? Either way, it is disappointing.

Few of us, and likely no marketing academics, will ever have the megaphone that Goodall has. Yet, it would be helpful if academics thought through their interventions into contentious political debates. Experts need to take public policy interventions seriously

Read: John Paul Tasker (2024) Climate warrior Jane Goodall isn’t sold on carbon taxes and electric vehicles, CBC News, April 13