Has A Manager Ever Used Tobin’s Q?

Ask an academic where they know Neil Bendle from and they might cite my work arguing that Accounting-based Approximations of Tobin’s q (AATQ) should never be used as a performance metric. (I don’t mean to imply that I think that I’m properly famous in the sense that normal people know who I am). I will reference my Marketing Science Article with Moeen Butt which outlines the argument against the use of Tobin’s q by marketing academics throughout this page. That said, I first want to ask a question: “Do Managers Ever Use Tobin’s q As A Dependent Variable?” Or in simpler terms, “Does any manager think that increasing Tobin’s q is their job?”

My experience suggests the answer is no. Indeed, Ofer Mintz and Imran Currim show negligible use of Tobin’s q in their Journal of Marketing article on metric use. (See more on their article here https://neilbendle.com/what-metrics-do-managers-use/). To be fair in their data there seems to be a solitary holdout claiming to use Tobin’s q. I’m guessing that was just yea-saying, some people really like to say yes when questioned. (Find these people and ask them for loans). Overall, Ofer Mintz and Imran Currim reported that Tobin’s q was not used by nine out of the ten groups of marketers. Indeed, it was the dead last metric in terms of overall usage.

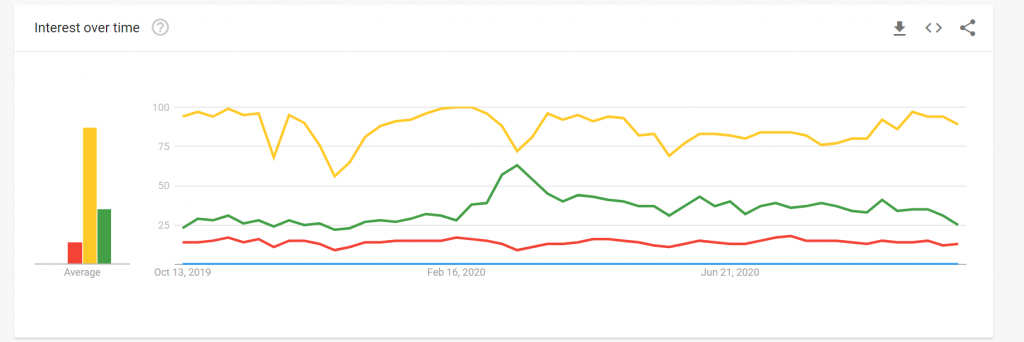

We Can See Tobin’s Q’s Lack of Real-World Relevance In Google Trends Data

I can summarize the Google Trend data below thus: Interest in Tobin’s q is largely absent in the general population.

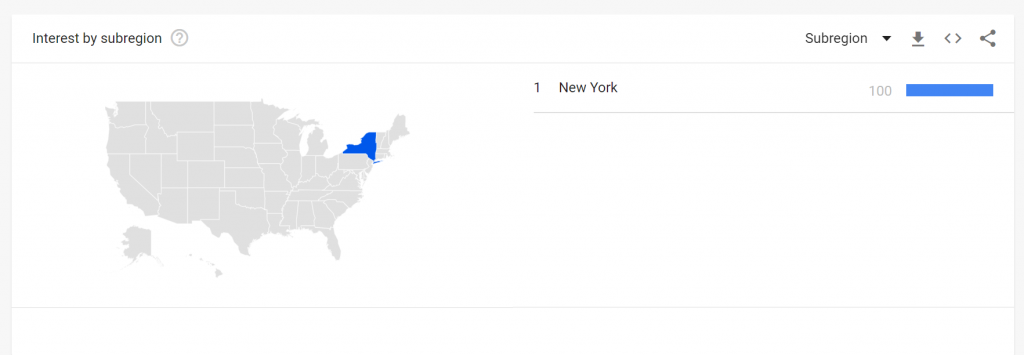

Interestingly, you can find where the people searching for metrics are based. For some reason, New York is the hub of Tobin’s q interest. (More specifically no one else seemed to search for it. What does this result mean? Let me conjecture about one really interested person in New York. Maybe instead it is a cabal of interested parties. (Did someone confuse Tobin’s q with QAnon?)

But Academics Have Made Extensive Use Of Tobin’s Q

Our 2018 Marketing Science outlines extensive use of Accounting-based Approximations of Tobin’s q in marketing.

Indeed, Edeling, Srinivasan, and Hanssens (2020) tells us that Tobin’s q is “the second most often used firm-value variable”. If managers don’t use it, why is it so popular with marketing academics? Surely academics should be using measures that business people recognize. As a matter of common sense, it is odd if academics say that a firm is doing great because it does well on a metric yet people who run the company, work in the company, and buy shares in the company don’t think that makes sense.

Accounting-based approximations of Tobin’s q (AATQ) are increasingly popular in marketing. AATQ differ from Tobin’s original conception in that they use accounting data to assess the replacement cost of a firm’s assets; the core problem with this is that valuable assets go unrecorded in external reports, including systematic under-recording of market-based assets.

Bendle and Butt, 2018, Abstract

Why Would Tobin’s Q Break-Through In Academia?

Accounting-based Approximations of Tobin’s q show bias towards finding marketing is successful. Why does that matter?

A thought experiment can illustrate the problem. As a researcher, you want to get an academic paper published and you find that your results show that marketing is unhelpful. Let’s be honest you are going to find it pretty hard to convince marketing reviewers to publish your results. This need not be conscious or malicious on the reviewers’ parts. All papers have flaws that reviewers choose not to make a big deal about. In consumer behavior research people often implicitly agree not to worry that student subjects aren’t representative, marketing strategy reviewers implicitly agree not too fuss too much about various imperfect proxies used, and analytical model reviewers implicitly agree not to push too hard on the assumptions made.

The point is that if you want, even subconsciously, to reject a paper you can. The reviewer can always have reasonable reasons to reject. Reviewers won’t necessarily mean to be harsh. It is just that they will push back when things aren’t what they expect — in this they are normal(ish) human beings. When performing research that shows marketing backfires your chance of publication goes right down.

Unfortunately, If You Find Nothing It Won’t Get Published

What if marketing does neither harm nor good? Who wants to publish this in any journal? Imagine writing, ‘we did a lot of work and found out that what we studied doesn’t matter at all’. It doesn’t seem like the greatest article to read.

Metrics that find the ‘right’ results are much more popular with academics.

Academia Can Be A Game Of Telephone

When one academic says something that builds credibility for the claims of future academics who cite it. This is a problem as initial mistakes get set into the record.

Furthermore, claims seem to progress in their casualness. In our paper, we highlight claims made about Accounting-Based Approximations of Tobin’s q. We observed in our paper that scholars claimed that these approximations, which by their nature contain accounting data, are superior metrics because they are not affected by accounting conventions. This is clearly and easily provably false. Our review showed that the claim started as saying that these Tobin’s q measures are not as much impacted by accounting conventions. It may not surprise the reader to learn that time did its damage and soon the ‘as much’ was just lost. Repetition builds credibility and soon marketers became used to reading articles that said metrics based upon accounting data were not impacted by accounting conventions. We called codswallop on this in our 2018 paper. If we hadn’t then maybe Tobin’s q would be curing cancer by now in the marketing literature.

Fields Evolve Towards Measures That Show Success

Think then what happens when a metric creates a publishable result. More students and professors get the idea that they should use it. Those that have used it become successful, they produce more work, and so others imitate them. Those that don’t use it are less successful.

Think of an evolutionary analogy, those who use Tobin’s q have more children. They replicate more and eventually take over the population displacing those who don’t use Tobin’s q.

Accounting-based Approximations of Tobin’s Q are Gresham’s metric. Using them drives out the use of good metrics. (Gresham’s law is that bad money drives out good). This is true at a superficial level, articles using Tobin’s q take up space in journals, but also at a deeper level where the field evolves towards the use of inappropriate metrics that gives more publishable results.

Doesn’t Usage Imply Progress?

At this point, it is worth noting that evolution does not imply progress. (See my piece in the Ivey Business Journal with Mark Vandenbosch and Ranjan Banerjee). Just because the market is evolving towards something does not imply this is better in some grand philosophical sense. As such, just because the marketing academic market moves towards use of Tobin’s q does not mean this is correct by some objective standard. This links to my quibble with asking marketing academics for their opinion on metrics which a recent paper did. Opinions don’t make a thing right or wrong; strong arguments for or against it do. (See more on this here.) As I said, asking those using the metric what they think of the metric is like asking witchfinders if witchfinding tools work.

Don’t Ask Witchfinders About The Validity Of Their Witchfinding Tools

Neil Bendle, What Can The Marketing–Finance Interface Tell Us About Witchcraft Trials?

It is especially challenging as the recent paper implies there is a debate going on. No one I have heard has responded to the criticisms in our 2018 article. I don’t mean people have responded but I didn’t accept their response. I mean there was no response. If only one side of a debate gives reasons there is no debate about whether Tobin’s q is a good performance measure being had. It isn’t a good performance metric and no one has given a meaningful argument otherwise.

You Can’t Just Rely On Social Proof

The justifications for use of Tobin’s q is that finance people use it. Tobin’s q isn’t as widely used as some imply. That said, I agree that the metric has been used in finance.

Yes, finance people often use the metric wrongly too but the finance scholars often use it differently. The problems in using Tobin’s q are certainly more acute in marketing. This is because of the nature of the assets that marketing creates — brands, customer relationships etc… What do financial accounts tend to omit? You have guessed it. Exactly these things. So the book value of firms is less accurate the more marketing the firm does.

Accounting-Based Approximations Of Tobin’s Q Not Useful As Performance Measures. Why?

Tobin’s q as an idea is interesting. Comparing market value of assets to the replacement cost of assets can in theory show when markets think assets are being used well or badly. (Of course, life is more complicated than that, but let us keep it simple).

Unfortunately, the replacement cost of assets is unknown in pretty much every situation. So the metric is simply not usable. The data you want does not exist and is nigh on impossible to create.

Scholars have hit upon the idea of using the book value of assets recorded in the financial accounts as replacement cost. Doing so probably seemed like a good idea to some people. The idea is to make practical Tobin’s original notion which was pretty theoretical. Yet using book value causes immense problems, and these problems are bleeding obvious to anyone who knows anything about financial accounting. The figures recorded in financial accounts have a plethora of biases. The replacement cost of assets used in AATQ is basically gibberish when looking at the assets of marketing heavy firms. This makes the Accounting-based Approximations of Tobin’s q metric wrong. There is no good reason why anyone would compare a theoretically meaningful number (market value) with one that is not meaningful (book value as a proxy for replacement cost)?

What Did Our 2018 Article Say?

This research examines the extensive erroneous claims made about AATQ in marketing studies. We note the widespread use of the metrics and demonstrate that the AATQ used in marketing (1) are not comparable across industries, (2) do not use only tangible assets in their denominator, and (3) should not find equilibrium at 1. AATQ are often described as performance metrics and can respond appropriately to certain types of positive performance. Unfortunately, they also respond positively to performance-neutral strategic choices. Furthermore, whenever AATQ exceed 1, as is typical, they increase even with completely wasted investments. We note that AATQ are especially problematic measures of performance for marketers because they are biased towards reporting that investments in market-based assets (e.g., brand equity and customer satisfaction) are effective. The misuse of AATQ we document suggests the need for marketing scholars to pay greater attention to the theoretical underpinnings of their metrics.

Bendle and Butt, 2018, Abstract

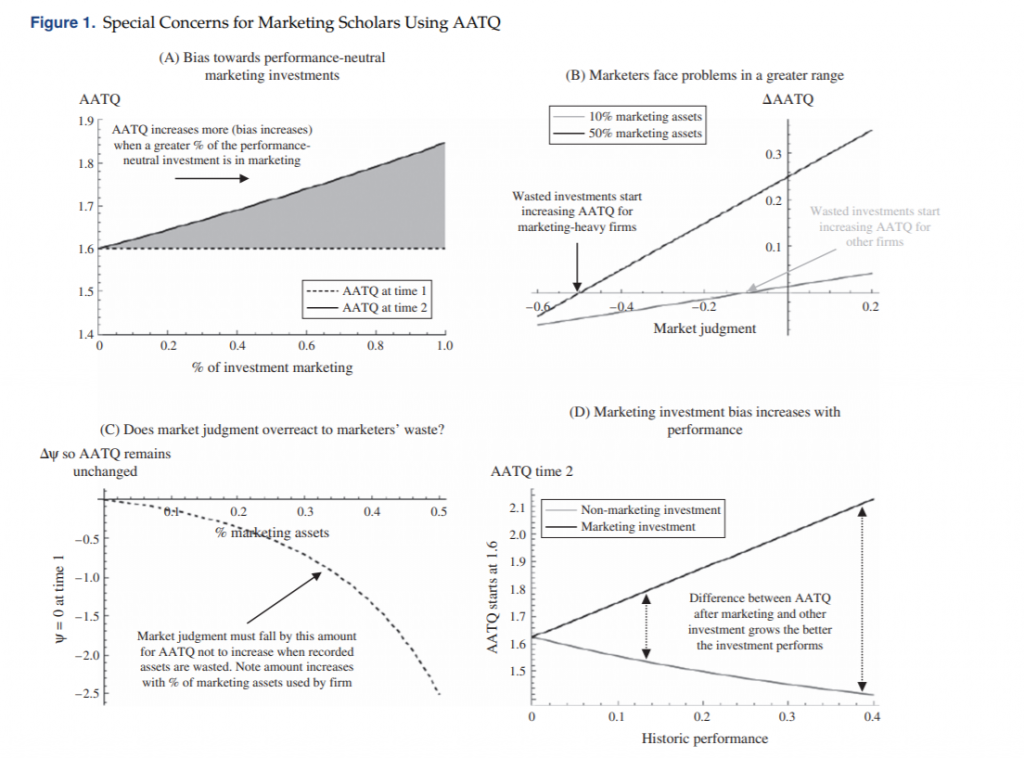

Marketing Has A Special Problem Using Tobin’s Q

Given marketing assets are more likely than most assets to be omitted from financial accounts marketing has a special problem with Tobin’s q.

- There is a bias towards showing marketing investments as better than they are. [The metrics tends to report marketing as successful].

- Tobin’s q has problems in a greater range of outcomes for marketers [than other scholars].

- Market judgment would have to overreact to marketing waste to compensate [which invalidates the theory behind using market value, another key input to Tobin’s q].

- The bias increases with performance [as firms do better the bias gets higher].

If You Want To Credibly Show The Value Of Marketing you Can’t Use A Non-Credible Measure

The challenge is much of the literature that uses Tobin’s q aims to show the value of marketing.

Marketing accountability research aims to examine marketing’s value; yet much of the research focuses on how marketing impacts AATQ, metrics that managers do not consider important. Attempts to build marketing’s credibility cannot be based on metrics that managers do not use and are biased towards finding marketing’s effectiveness. Researchers should use metrics that are meaningful to non-researchers or, at a minimum, argue in detail why the metrics should be meaningful to non-researchers.

Bendle and Butt, 2018, page 34.

This brings me back to where I started. Without knowing anything about the metric you should always be suspicious when you don’t see the metric in everyday use. Demonstrating the value of something but using a measure that no one uses is pretty strange. There might be reasons for doing it in unusual circumstances. That said, in academic marketing research you need a pretty good justification for using a measure to show the value of what you do that no business person has ever cared about.

For more on Tobin’s q see

More on the gradually increasing use of Tobin’s q.