In marketing, we often refer to averages. Indeed, the average does matter. “What does the average person think?”, is often a reasonable enough question to start. Plus, higher average preference is usually better than lower. Unfortunately, this can risk obscuring the fact that the distribution of preferences also matters.

Polarizing Brands

Xueming Luo, Michael Wiles, and Sascha Raithel discussed the challenges and benefits of polarizing brands in a 2013 Harvard Business Review (HBR) article. They note that some brands polarize opinions – some people love the brand while others hate the brand. They give the example of Miracle Whip. I must confess I have never eaten Miracle Whip but I can believe there are plenty of people who don’t like it. And it does sound quite weird. I guess there are also some people who like it, but that isn’t as believable to me.

In the UK people refer to something being like Marmite. This is another strange spread. It is visually unappealing and unpleasant tasting but some people say they love it. (There seems to me a reasonable chance that this expressed preference is just to mess with other people). Anyhow, the point is that there certainly are brands that polarize opinion.

Distribution Of Preferences Matters

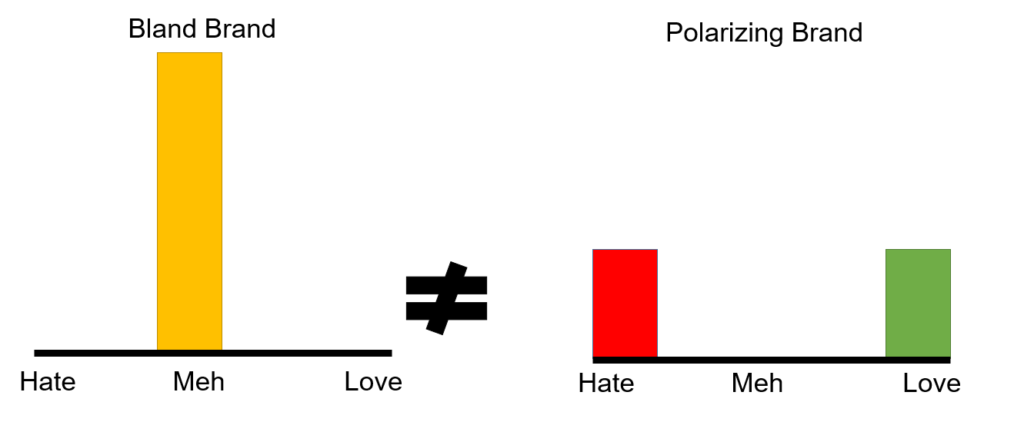

This leads to a challenge in that we often talk about averages, yet, averages can be misleading. A brand that some love and some hate could well have the same average response as a brand everyone has absolutely no reaction towards. Having some supporters and some opponents is not the same as a load of ambivalent respondents.

Which Is Better?

It depends upon circumstances whether it is best to be bland or polarizing from a business perspective. The authors argue that:

…highly polarizing brands tend to perform more poorly than others, but they also tend to be less risky—to exhibit relatively little variation in stock price.

Luo, Wiles, and Raithel (2023)

To be honest, I’m not a fan of generalizations such as that. It seems that observed performance will depend a lot upon your analytical choices including what data you included in your analysis and what you did not. Plus, a big challenge with HBR articles is that they don’t give enough detail about the analysis to draw many conclusions. Still, it is an interesting idea and that polarizing brands are less risky is somewhat intuitive. People have made up their minds, new experiences won’t budge them much.

As an aside, US politics seems to resemble a polarized market currently. People seem to have made up their minds on Donald Trump and Joe Biden and aren’t shifting that much. These seem to be the candidates that Americans will have to choose between for president in 2024. While many have negative things to say about this choice, I see a heartwarmingly positive silver lining emerging from the competition between these two candidates. It affirms the old American adage that anyone can be president. What is more that adage holds even if you are unpopular at record levels and most people don’t want you to be president.

What To Do If You Have A Polarizing Brand?

There certainly can be advantages to having a polarizing brand. You can gain attention, you can separate yourself from rivals, you might even lean into the polarizing attribute to drive attention and loyalty.

Indeed, their advice about getting beyond averages is very important.

Managers should avoid relying on averages; they need to dig deeper to uncover and understand the full range of attitudes towards their products. Although this is especially critical for polarizing brands, all firms should be cognizant of their brand’s dispersion [distribution of reactions] and should track it over time.

Luo, Wiles, and Raithel (2023)

If you have a polarizing brand there can be advantages. Why not see how you can benefit from them rather than becoming just another boring brand?

For more on the importance of variance see here and here

Read: Xueming Luo, Michael Wiles, and Sascha Raithel (2013) Make the Most of a Polarizing Brand , Harvard Business Review, November