There is a wonderful 2003 Science article about how people react to default choices. The conclusion? Defaults matter.

Why Does This Matter?

The article impresses for a number of reasons including:

- Saving lives matters.

- While it is not a theory paper the theoretical implications are substantial. What are people’s preferences — what they say or what they do?

- The paper is short. The authors do more in two pages than most do in twenty.

- There are different data types used, experiment and real-life data. Testing using multiple methods is convincing.

In Organ Donations Defaults Matter

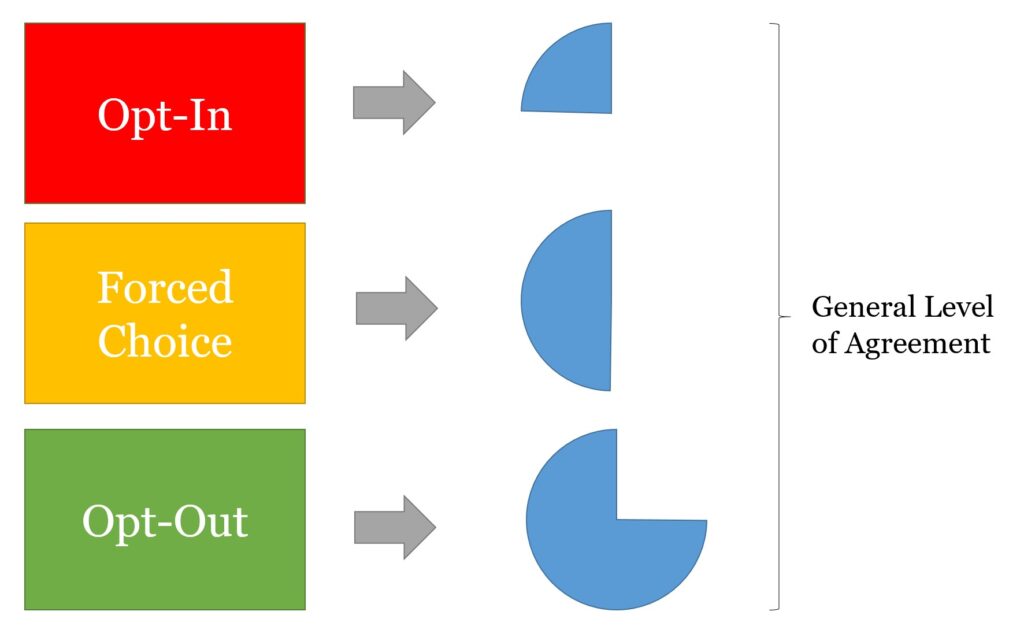

So what does the article say? In organ donations the default option matters. When people must opt-in (explicitly consent) to donate very few people opt-in. Yet when they must opt-out (explicit reject donating) very few opt-out. In Germany, opt-in, the effective consent rate was 12% while in Austria, opt-out, the effective consent rate was 99.98% (Johnson and Goldstein 2003). Of course, there are other potential explanations and people can pick at the results. Still, the effect is massive, suggesting that the government’s choice of default option makes a difference. This is “nudging”; encouraging people to pro-social choices by the way the decision is structured.

What does this mean? That people don’t have strong enough preferences to overcome the default. Probably somewhat but costs were very low. People probably also don’t like to think about death. We may do everyone a favor by encouraging them to take the pro-social option without having to think about their mortality. Finally, people enjoy copying what most do. The default indicates the “normal” choice.

Forced Choice May Help

Good news: people mostly choose to donate when a choice is forced. This suggests they want to donate but just won’t opt-in. Making donations opt-out saves lives and makes people feel better about themselves. Those with serious objections to donation, e.g. for religious reasons, can still opt-out if they want to for some reason.

The lesson: structure decisions to help pro-social choices. If we save lives by changing from opt-in to opt-out, why wouldn’t we? There are significant implications beyond medicine. Why not make pension deductions automatic? Objectors can still opt-out, (mostly they won’t and will likely be better for it).

Businesses can structure decisions to make the default what the marketer wants. The obvious reflection is that consumers should realize that the default is what the marketer wants. (Assuming the marketer is good at their job). That does not make the default bad. The marketer’s incentive is just something that the consumer should be bearing in mind.

For more on decision-making see here and here.

Read: Eric Johnson and Dan Goldstein, Do Defaults Save Lives? Science 21 November 2003.